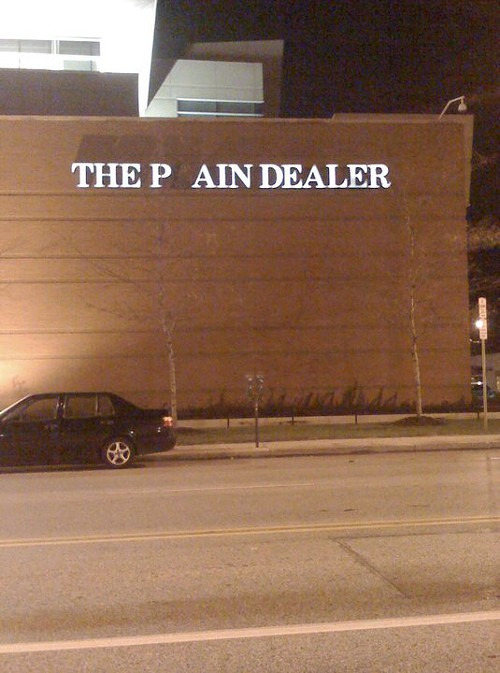

Ten years ago there were 300 journalists working in the Plain Dealer newsroom. Now, after 22 more of them lost their jobs last Friday in yet another round of layoffs by the paper’s corporate owner Advance Media, there are only 14 left. According to a statement issued by the PD News Guild, the nation’s first reporters’ union, “Advance has methodically reduced the number of journalists [at] the Guild-represented PD, while boosting the presence of its non-union newsroom at cleveland.com,” where 63 journalists remain. Thus, what Cleveland Scene’s Sam Allard calls the “ridiculous schism” orchestrated by Advance between the PD and Cleveland.com newsrooms has essentially fulfilled its purpose of “crush[ing] the PD union.”

While these developments aren’t especially surprising to anyone who’s been following the newspaper industry, and Advance Media in particular, over the last decade or so, it’s worth a pause to contemplate what it means when so much of an industry whose main purpose is to speak truth to power is controlled by famously anti-union multibillionaires—in this case, the New York, NY-based Newhouse family, Advance Media’s owners whose combined fortune is estimated to be worth more than $16 billion.

It’s perhaps also unsurprising, if especially relevant, that the patriarch of the Newhouse fortune, Samuel Irving Newhouse, built it largely by consolidating local newspapers nationwide into local monopolies, which shortly became “gold mines to own.” The monopoly that Newhouses obtained in Cleveland was reportedly among his most profitable.

According to a 1987 profile of the family by Carol Loomis in Fortune Magazine, the Plain Dealer’s “old competitor, the Cleveland Press, folded in 1982 amid charges that the Newhouses had induced its closing by agreeing to pay its owners $22.5 million for assets that were essentially worthless.” Two ex-employees of the press shortly sued the Newhouses for “conspiracy with intent to create a monopoly” but the lawsuit was dismissed before trial because, while “the judge thought the charge might be on target, she did not believe the employees were the right plaintiffs.” Additionally, a Department of Justice Lawyer, after being fired, publicly announced that the Department’s lengthy investigation of the charge was “halfhearted.” As a result, the PD’s daily circulation and ad rates spiked, and by 1987 it was reported to be “the second most profitable Newhouse paper” out of dozens, “after years of earning little or nothing.”

Needless to say, at this point it should have been clear enough that running newspapers primarily to make a profit was inconsistent with the democratic objectives of journalism: that “the market simply can’t support the levels of journalism — especially local, but also international, policy, and investigative reporting — that a healthy democracy requires.” University of Pennsylvania professor Victor Pickard, writing in the Harvard Business Review, has excellently summarized the political economy of this crisis:

In the U.S., most commercial media organizations rely on revenues from delivering our attention to advertisers. Throughout much of the 20th century, newspapers typically derived 80% of their revenue from advertisers and 20% from readers. For decades this arrangement was tremendously profitable for newspaper publishers, who sometimes were willing to fund more expensive kinds of reporting. However, this economic relationship masked a key reality: Advertisers’ main objective wasn’t to ensure that democratic society had sufficient journalism. They weren’t concerned with whether the local school board was being covered, or if a foreign news bureau operated overseas. Advertisers were after audiences, and newspapers were a convenient vehicle for reaching them. News was, in many ways, a by-product of the main exchange.

This was a partnership of convenience — a happy accident — that camouflaged what was in fact an unnatural union. For this and other reasons, journalism has always been prone to market failure. Overreliance on a single mode of revenue exposed news institutions to enormous risk. That longstanding vulnerability became painfully clear with the advent of the internet.

As consumers and advertisers migrated to the web, where digital ads pay pennies to the dollar of traditional print ads (and most of that money goes to Google and Facebook), the 150-year-old business model for commercial newspapers imploded. Over the past two decades, the newspaper industry is estimated to have lost tens of billions of dollars in advertising revenue. In response, beleaguered papers have continuously cut costs, often in the form of layoffs or buyouts of journalists. (The number of newspaper employees has declined by more than half since the early 2000s.) Newspapers are declaring bankruptcy, reducing home deliveries, or going online-only. This devaluation gives readers fewer incentives to support local news, which accelerates a vicious race to the bottom.

Rushing into the vacuum left by our vanishing local news outlets are various forms of disinformation. At the same time, people are increasingly gleaning news from social media, through which misinformation abounds. Without profound structural changes, our media landscape will produce more noise and propaganda and less fact-based reporting—more shouting heads and hot takes and less actual journalism.

Of course, if this weren’t bad enough, the market failures of the journalism industry were exacerbated by and also surely helped bring about the “wip[ing] away [of] a century of campaign finance regulations designed to prevent corporations and business alliances from using their immense resources to buy the results that best serve their interests.” This was easy enough to see in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which obliterated existing limits on campaign spending in 2010, leading to what industry experts John Nichols and Robert McChesney observed, with stunningly predictive accuracy, the emergence of a “new normal”:

[One] in which consultants dealing in dollar amounts unprecedented in American history use “independent” expenditures to tip the balance of elections in favor of their clients. Unchecked by even rudimentary campaign finance regulation, unchallenged by a journalism sufficient to identify and expose abuses of the electoral process and abetted by commercial broadcasters that this year pocketed $3 billion in political ad revenues, the money-and-media election complex was a nearly unbeatable force in 2010. …

The narrative for the most part still comes from broadcast and cable TV stations, as it has for some time, but it is now produced and paid for by economic elites that seek to define not just the results of an election but the scope and character of government itself.

[E]ven serious analysts tended to underestimate the speed with which corporate interests and wealthy conservatives would take advantage of the severe damage done to campaign finance laws. The corporate intervention was unapologetic. “The big three stepping into the batter’s box are the financial services industry, the energy industry and the health insurance industry,” chirped veteran GOP operative Scott Reed, whose Commission on Hope, Growth and Opportunity spent millions, perhaps tens of millions, this fall on thousands of commercials attacking Democratic lawmakers in battleground states all over the country.

“We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both,” observed Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis. America is being put to the Brandeis test: democracy or plutocracy. The money-and-media election complex is creating a radically different electoral landscape than anything Americans have known since the Gilded Age. That landscape is characterized, pundits tell us, by an “enthusiasm gap.” No kidding. Americans are not stupid. They knew their relatively paltry contributions, and even their votes, were unlikely to stop a $4 billion onslaught. To those bankrolling the system, voter cynicism and apathy are welcome. The more that the 2008 surge of youth participation in electoral politics dissipates, the better for them.

But it’s not just corporations and consultants who are setting the new agenda. The most important yet least-recognized piece of the money-and-media election complex is the commercial broadcasting industry, which just had its best money-making election season ever. Political advertising has become an enormous cash cow for it—roughly two-thirds of the campaign spending this year flowed into the coffers of TV stations; the final figure is likely to be well above $2 billion. Whereas in the 1990s the average commercial TV station received about 3 percent of its revenues from campaign ads, this year campaign money could account for as much as 20 percent. And station owners are not missing a beat; thirty-second spots that went for $2,000 in 2008 were jacked up to $5,000 this year, according to the Los Angeles Times. Much of this money will go to stations owned by a handful of Fortune 500 firms. No wonder station owners oppose campaign finance reform; their lobby role in Washington is similar to the NRA’s in battling bans on assault weapons.

The same results have naturally played out at the state level as well, where, according to a Pew survey, the number of statehouse reporters nationwide collapsed by 35% between 2004 and 2014, and has surely only dwindled in years since. Thus, as Nichols describes it, “our political campaigns are guided by out-of-state donors and consultants, not candidates and voters, our legislative chambers are gerrymandered, [and] our court races are politicized in ways that are dramatically at odds with how they were designed to be run.”

If it was clear enough in 2010 that “determined and dramatic responses are the only options if we hope to maintain anything more than the remnants of a functioning democracy,” this of course has only become much clearer since. Fortunately, what such a response would have to start with is also clear: A well-funded public media system, as described by Pickard in the Harvard Business Review piece linked above:

Many democracies around the world maintain strong public media systems. In these countries, news and information are treated as what economists might call a public or merit good — a public service that the private sector is unlikely to provide because it is unprofitable and consumers are unable or unwilling to pay for it. (Other examples include education, health care, defense, and infrastructure.) Since public goods often yield tremendous benefits for all of society, and since healthy democracies depend on them, the state supports what markets can’t.

The U.S., however, tends to treat news and information more like commodities than public goods. And it’s a global outlier among democracies for how little it spends on public media. The U.S. federal government allocates around $1.35 per person per year for public broadcasting, while Japan spends over $40 per citizen, the UK about $100, and Norway over $176.

Why does it matter that the American system is so underfunded? Lack of taxpayer support forces public broadcasting to rely more on wealthy donors and corporate underwriters, making it less responsive to public needs and less likely to take on powerful interests. In addition, without a well-financed public media system, there’s no safety net for when the market fails to support the local news media that democracy requires. We must expand on and repurpose America’s public broadcasting system to serve as a core democratic infrastructure, one that provides news and information as well as cultural and educational fare, to everyone across all platforms and media types.

Works Progress Administration programs from the 1930s, such as the Federal Theatre Project and the Federal Writers’ Project, which helped put unemployed artists back to work, could provide a blueprint for reemploying legions of journalists. Another compelling experiment was Los Angeles’s taxpayer-supported municipal newspaper, described as a “people’s newspaper,” which was established in 1912 to cover gaps in the commercial press’s coverage.

Pickard is also surely correct that building the infrastructure for a functioning public media system “will be a long, hard slog,” that will only be achieved by understanding “the market as journalism’s destroyer, not its savior,” and the need to “rescu[e] journalism from commercial forces.”

While Sam Newhouse couldn’t have predicted the destruction he would cause in embarking on his Horatio Alger journey a century ago, his heirs are more than capable of understanding it today. If it’s going to take the help of enlightened billionaires to fix this crisis (it gets harder every day to believe that it won’t), if my name were Newhouse I would be doing whatever I could to be one of them. This is a problem that the majority of people are just beginning to understand, but it’s hardly unfixable. We didn’t get FDR until the Great Depression was well underway, but we should have also learned plenty since then.

Anyway, in the meantime, solidarity to the journalists at the PD who just lost their jobs, many of whom were among the most beloved and capable in the State, as well as to journalists everywhere.