UPDATE: For a much more comprehensive treatment of the subject, click here.

UPDATE: For a much more comprehensive treatment of the subject, click here.

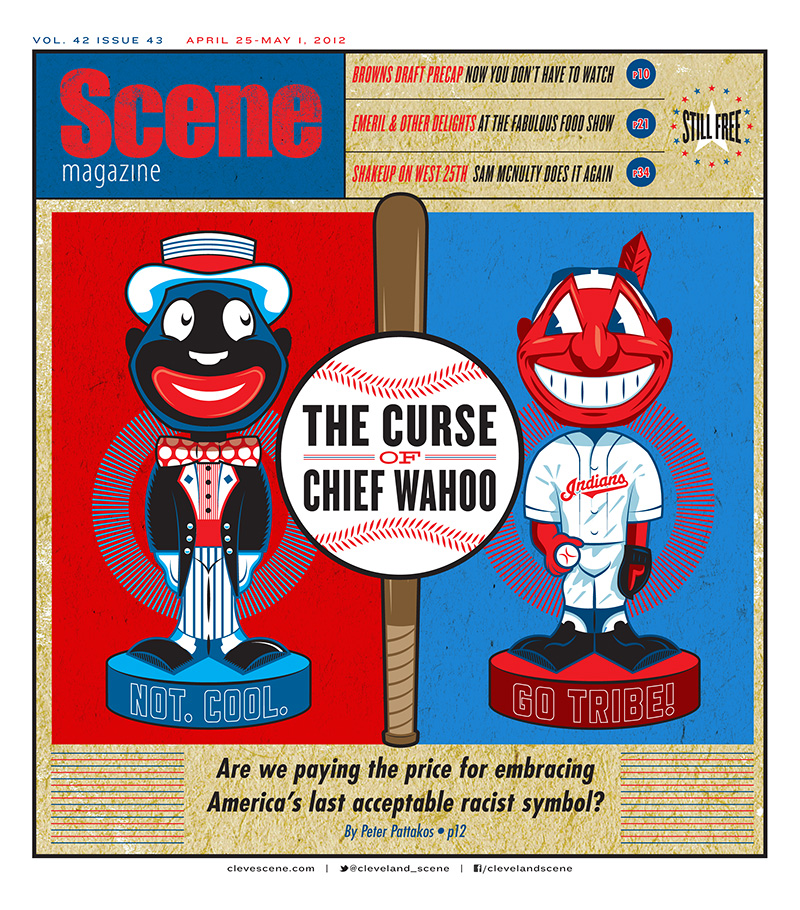

Whatever else about Chief Wahoo, the face of the Cleveland Indians, it’s amazing that we don’t hear more about a “Curse of Wahoo” in Cleveland, the city suffering the longest and most painful championship drought in major American professional sports. Surveys show that an overwhelming majority of Americans prefer to believe in some metaphysical order, so it’s no surprise that as bad results accumulate, speculation about the metaphysical source of those results — a curse — is soon to follow. So, if the Boston Red Sox had to endure an 86-year curse for trading Babe Ruth, and if the Chicago Cubs have been cursed for the last 63 years simply because they wouldn’t let a guy bring his goat into the stands at Wrigley Field, why don’t we hear more about the Indians, if not all Cleveland franchises, being cursed for what’s so easy to see as an affront to Native Americans and disrespectful of the beginnings of American history?

Most likely because for a great many, if not most, Indians fans, Chief Wahoo represents something entirely different. It’s long past time for us to come to terms with the Chief, and this won’t happen until the activists and others who are so convinced of Wahoo’s evil can understand the good that he represents to so many others.

To understand why Wahoo has survived for so long in this world that long ago turned Bullets into Wizards, and Redskins and Redmen into Red Hawks and a Red Storm, one has to understand that for so many Tribe fans, Wahoo represents the very best of “Take me out to the Ballgame.” In Northeast Ohio, one can live in beautiful country that’s only a short trip away from a relatively big city. It’s no surprise that many choose to do this. And because such a small percentage of Tribe fans live in Cleveland proper, so much of the joy of going to a ballgame is inseparable with the joy of coming to the big city on the big lake. For so many of us, our first trips to the Stadium were our first times in any real city. So many of us can remember the wonder that came with seeing the bridges over the Cuyahoga for the first time, standing in the Flats and looking up at the city on the cliff, or craning our necks to try to see the top of the first skyscrapers that we’d ever seen. Our folks wanted to save on parking, so we walked from the Terminal Tower, the Muni Lot, the Flats, or the workaday lots east of 9th street, and we made the trek through the city to the Stadium together with so many others of all shapes and colors. And we saw, many of us for the first time, that those people were no different from us – at least because we all wanted the home team to win.

To understand why Wahoo has survived for so long in this world that long ago turned Bullets into Wizards, and Redskins and Redmen into Red Hawks and a Red Storm, one has to understand that for so many Tribe fans, Wahoo represents the very best of “Take me out to the Ballgame.” In Northeast Ohio, one can live in beautiful country that’s only a short trip away from a relatively big city. It’s no surprise that many choose to do this. And because such a small percentage of Tribe fans live in Cleveland proper, so much of the joy of going to a ballgame is inseparable with the joy of coming to the big city on the big lake. For so many of us, our first trips to the Stadium were our first times in any real city. So many of us can remember the wonder that came with seeing the bridges over the Cuyahoga for the first time, standing in the Flats and looking up at the city on the cliff, or craning our necks to try to see the top of the first skyscrapers that we’d ever seen. Our folks wanted to save on parking, so we walked from the Terminal Tower, the Muni Lot, the Flats, or the workaday lots east of 9th street, and we made the trek through the city to the Stadium together with so many others of all shapes and colors. And we saw, many of us for the first time, that those people were no different from us – at least because we all wanted the home team to win.

And at the end of this fascinating trek, as we crossed Route 2 and approached the magnificent structure on the lake, we saw it; the 35-foot tall neon-lit Chief Wahoo of glass and steel, perched atop the southeast corner of the Stadium roof, eyes gleaming, smile beaming, bat cocked, leg raised, ready to knock the next pitch down to Youngstown. And we didn’t think of Native Americans, or any kind of person at all. So much of the magic of the trip to the ballpark coalesced in that smiling slugging alien angel of joy as we entered the Stadium gates. And then there was the magic of the game itself, with Wahoo smiling in approval all the while — from the stadium roof, our heroes’ uniforms, and seemingly everywhere else. Indians executive Bob DiBiasio touched on this when he told the New York Daily News in March 2007 that, “[w]hen some people look at our logo they see baseball . . . They see Bob Feller and Omar Vizquel and Larry Doby.”

And at the end of this fascinating trek, as we crossed Route 2 and approached the magnificent structure on the lake, we saw it; the 35-foot tall neon-lit Chief Wahoo of glass and steel, perched atop the southeast corner of the Stadium roof, eyes gleaming, smile beaming, bat cocked, leg raised, ready to knock the next pitch down to Youngstown. And we didn’t think of Native Americans, or any kind of person at all. So much of the magic of the trip to the ballpark coalesced in that smiling slugging alien angel of joy as we entered the Stadium gates. And then there was the magic of the game itself, with Wahoo smiling in approval all the while — from the stadium roof, our heroes’ uniforms, and seemingly everywhere else. Indians executive Bob DiBiasio touched on this when he told the New York Daily News in March 2007 that, “[w]hen some people look at our logo they see baseball . . . They see Bob Feller and Omar Vizquel and Larry Doby.”

Those who want to bury Wahoo have to acknowledge why he’s lasted so long — that in doing so they would be burying more than a racist caricature; they would be burying a part of our childhood and our culture. They have to acknowledge that the collective attachment to Wahoo has little to nothing to do with an intent to disparage a race of people. So much of the resistance to attempts to get rid of Wahoo is a natural reaction by Tribe fans in response to what they see as an assault on those magical trips to the ballgame. Activists must acknowledge the innocent aspects of our attachment to Wahoo before their appeals to his harmful effect will ever be well-received.

Once Tribe fans believe that our love for Wahoo is understood, we’ll be more apt to ask ourselves why we would want to be attached any longer to a symbol as potentially demeaning to a race of people as Wahoo is.

An honest examination of Wahoo’s origins would be a good place to start. Any such look back puts lie to the company line that the Cleveland baseball franchise was named “Indians” to honor former Cleveland second baseman Louis Sockalexis, the first Native American to play Major League Baseball. According to an October 2007 story in a Maine newspaper, the Kennebec Journal, for which the reporter interviewed the author of a book on Sockalexis, Sockalexis’ arrival in Cleveland in 1897 “created such a stir that local newspapers jokingly dubbed his team, the Cleveland Spiders, the ‘Cleveland Indians.’” This was not done to honor Sockalexis’ Native American heritage, but rather because, “[r]acism was accepted in journalism in that day . . . Sportswriters would write things like, ‘He’s gonna be scalping people.'” Sockalexis was “burdened by alcohol abuse and racist taunts from opposing players and fans,” and his time with the Indians was short, ending in 1899.

An honest examination of Wahoo’s origins would be a good place to start. Any such look back puts lie to the company line that the Cleveland baseball franchise was named “Indians” to honor former Cleveland second baseman Louis Sockalexis, the first Native American to play Major League Baseball. According to an October 2007 story in a Maine newspaper, the Kennebec Journal, for which the reporter interviewed the author of a book on Sockalexis, Sockalexis’ arrival in Cleveland in 1897 “created such a stir that local newspapers jokingly dubbed his team, the Cleveland Spiders, the ‘Cleveland Indians.’” This was not done to honor Sockalexis’ Native American heritage, but rather because, “[r]acism was accepted in journalism in that day . . . Sportswriters would write things like, ‘He’s gonna be scalping people.'” Sockalexis was “burdened by alcohol abuse and racist taunts from opposing players and fans,” and his time with the Indians was short, ending in 1899.

In 1915, two years after Sockalexis’ death, the president of the Cleveland ball club enlisted the help of local sportswriters to rename the team, then called the “Naps” after star Napoleon “Nap” Lajoie, who had recently been traded to Oakland. The name “Indians” was chosen by the sportswriters in a decision that can most charitably be described as motivated by sensationalism, if not base hatred. According to research conducted by the Committee of 500 Years of Dignity and Resistance, none of the four daily Cleveland newspapers mentioned Sockalexis in reporting the name change. Three of these four reports (available here) do, however, refer to stereotypes about Native Americans. A January 17, 1915 report in the Cleveland Leader reported that “[i]n place of the Naps, we’ll have the Indians, on the warpath all the time, and eager for scalps to dangle at their belts.” The Plain Dealer of the same day included a cartoon titled “Ki Yi Waugh Woop! They’re Indians.” This cartoon (pictured above) depicts, among other things, a frowning umpire scolding a Native American: “When you talk to me, talk English, you wukoig.” “Wukoig,” according to the Plain Dealer cartoon, is an “Indian” word.

With Wahoo standing alone as the only racist caricature currently accepted in American society, it’s hard to tell Natives like the ones quoted above to “lighten up.” Yet redface is alive and well here in Cleveland. How else to explain this disparity if Ms. Teters isn’t at least partially right about the invisibility of Natives in America? So why would we want to be a part of reinforcing this invisibility? An insensitivity to these issues that was more understandable in the less integrated society of our parents’ day has to be much less so now. At some point our intention – the innocence behind our attachment to Wahoo — stops mattering.

With Wahoo standing alone as the only racist caricature currently accepted in American society, it’s hard to tell Natives like the ones quoted above to “lighten up.” Yet redface is alive and well here in Cleveland. How else to explain this disparity if Ms. Teters isn’t at least partially right about the invisibility of Natives in America? So why would we want to be a part of reinforcing this invisibility? An insensitivity to these issues that was more understandable in the less integrated society of our parents’ day has to be much less so now. At some point our intention – the innocence behind our attachment to Wahoo — stops mattering.

Which brings us back to the Curse. Native voices have told us loudly and clearly that Wahoo offends; and given his origins and singular status among racial caricatures in America, it’s not at all hard to see how this might be true. If there is at least one Native in this country for whom Wahoo reasonably reinforces a belief that her or his race is invisible or subhuman — thus making it even a little bit harder to engage in life’s everyday struggle — isn’t that enough to bring a curse on our sports teams? It sure seems worse than trading Babe Ruth or banning goats from a ballpark. So why would we even want to take this chance? Haven’t we all had enough of the exquisitely painful losing? There are a lot of Natives buried in these parts. If it’s not the Curse of Chief Wahoo, what else could it be? What else would we want it to be? At least a Curse of Chief Wahoo makes sense. At least it’s a curse that we might do something to end.

Which brings us back to the Curse. Native voices have told us loudly and clearly that Wahoo offends; and given his origins and singular status among racial caricatures in America, it’s not at all hard to see how this might be true. If there is at least one Native in this country for whom Wahoo reasonably reinforces a belief that her or his race is invisible or subhuman — thus making it even a little bit harder to engage in life’s everyday struggle — isn’t that enough to bring a curse on our sports teams? It sure seems worse than trading Babe Ruth or banning goats from a ballpark. So why would we even want to take this chance? Haven’t we all had enough of the exquisitely painful losing? There are a lot of Natives buried in these parts. If it’s not the Curse of Chief Wahoo, what else could it be? What else would we want it to be? At least a Curse of Chief Wahoo makes sense. At least it’s a curse that we might do something to end.

So why not hesitate in giving Wahoo a dignified burial? In doing so, we should recognize that while Wahoo might have been born out of something bad, he turned into something very good for many of us. We should acknowledge the complexity of the lives of both persons and personifications. And we should acknowledge progress. There’s certainly no shortage of Northeast Ohio natives who’d be worthy models for a new logo; one that truly honors Native Americans.

So why not hesitate in giving Wahoo a dignified burial? In doing so, we should recognize that while Wahoo might have been born out of something bad, he turned into something very good for many of us. We should acknowledge the complexity of the lives of both persons and personifications. And we should acknowledge progress. There’s certainly no shortage of Northeast Ohio natives who’d be worthy models for a new logo; one that truly honors Native Americans.