It makes sense that it was a legendary muckraking journalist, Upton Sinclair, who coined the truism about how hard it is “to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” And it’s not so surprising after Advance Media’s brutal round of union-busting layoffs at the Plain Dealer last week that the company’s top editor in Cleveland, Chris Quinn, is having a tough time understanding, or pretending to not understand, why everyone is so upset.

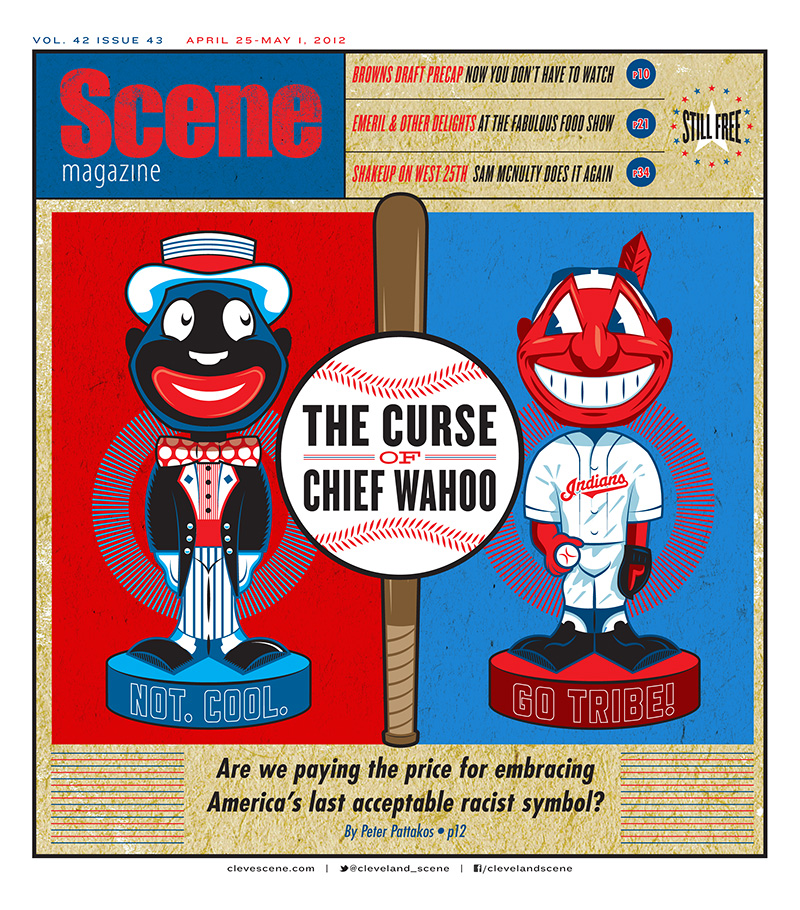

With last week’s layoffs having completed a process by which a PD newsroom of 350 union-backed journalists has been decimated, over a decade, to 63 non-union reporters under the banner of Cleveland.com, there has naturally been an outcry over the death of journalism in Cleveland. As Sam Allard observed last week in a scathing assessment of these developments at Cleveland Scene, an already overburdened Cleveland.com newsroom is now much more so, with legitimate journalism sure to be increasingly “drowned out by torrents of brain-numbing clickbait and sponsored content, and further cheapened by a truly abominable social media presence.” And with news outlets nationwide having been subject to similar cuts, it’s been widely observed that “our political campaigns are [increasingly] guided by out-of-state donors and consultants, not candidates and voters, our legislative chambers are gerrymandered, [and] our court races are politicized in ways that are dramatically at odds with how they were designed to be run.”

In other words, with 80% fewer journalists in Cleveland to fulfill the essential function of uncovering stories to inform the public, it stands to basic reason that the public will be 80% less informed.

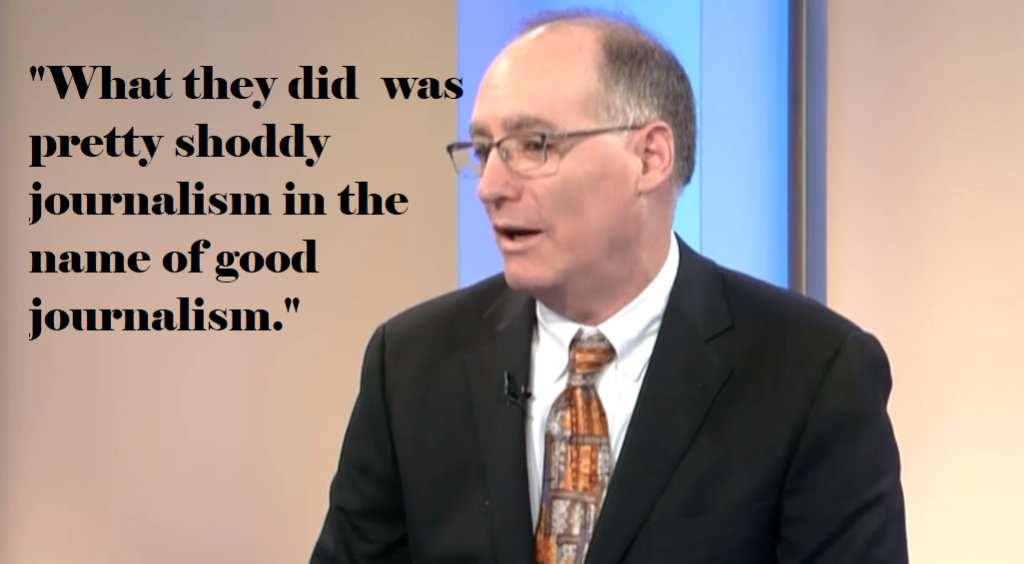

The problem here is obvious and critical. To everyone but Quinn, anyway, who took to the pages of Cleveland.com yesterday to pen a wildly defensive and Orwellian column claiming not only that journalism isn’t “dying in Cleveland” but that in fact it “thrives,” and anyone suggesting otherwise has “dubious motives,” and “appear[s] to be unafflicted by truth.” The relevant paragraphs, where Quinn also lashed out at critics, former colleagues, and the very notion of adversarial journalism, are as follows:

You couldn’t be blamed for not knowing the reporters and editors at cleveland.com. They don’t build cult followings on social media with nonstop messages about their crusading roles. They believe that journalism is about what others do and don’t use social media to call attention to themselves.

The people I work with just keep their heads down and produce the stories, photos, audio and video that you so clearly value — you engage with it in huge numbers.

I find so much dignity in my cleveland.com colleagues. They do the work. Diligently. Accurately. With quiet determination. Without bias.

There’s a danger in your not getting to know them, though. Some people with dubious motives – people who appear to be unafflicted by truth — would have you believe that journalism is dying in Cleveland. That’s false, of course, as any objective review of cleveland.com’s coronavirus coverage would prove. Journalism thrives in Cleveland in the form of our 60-plus reporters and editors.

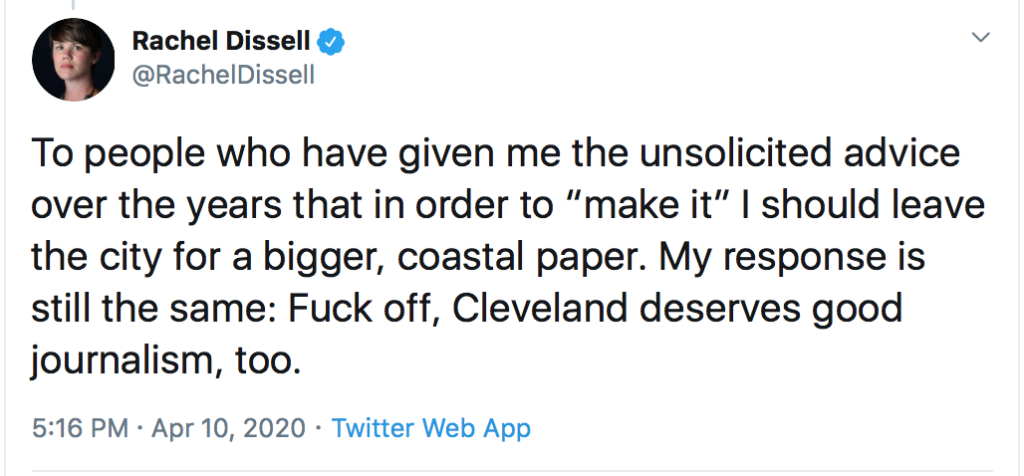

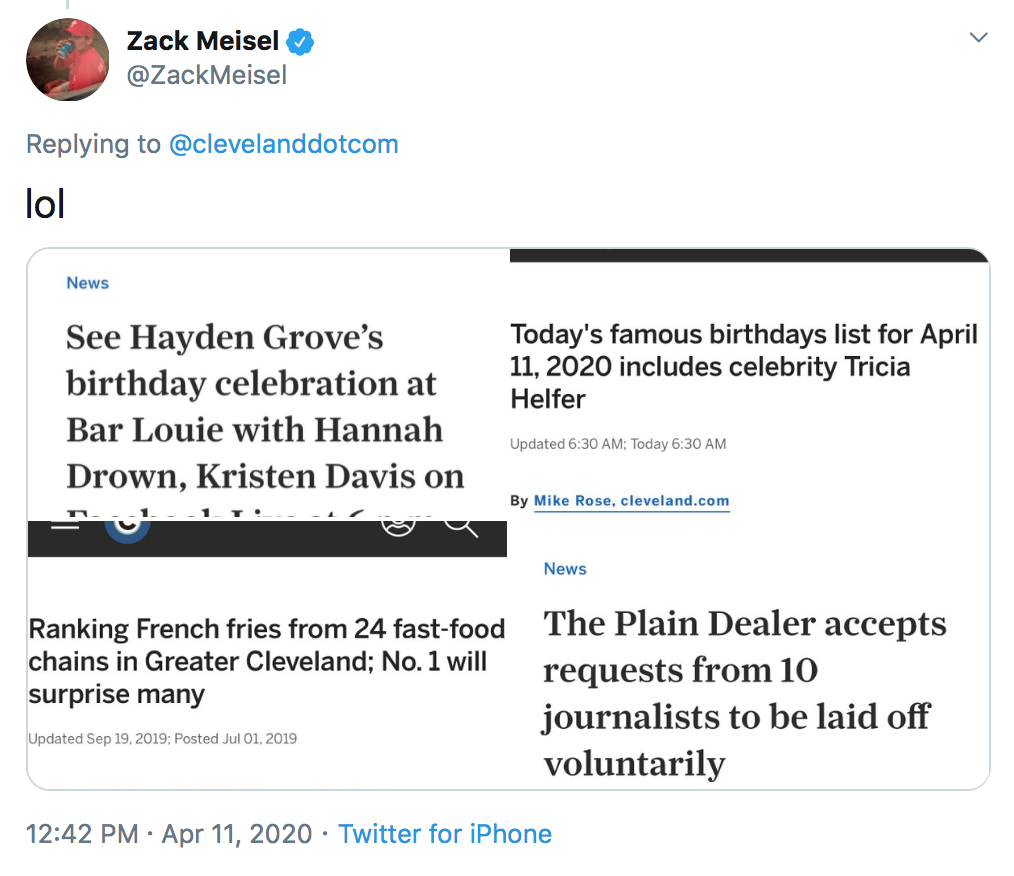

Quinn’s column was met with immediate derision, with accomplished veteran journalists like L.A. Times City Editor Hector Berrerra calling it a “dumpster fire,” and Tampa Bay Times reporter Mark Puente citing the piece as an example of “delirious newsroom leader[ship],” while pointing out that Quinn was once a “hard-nosed reporter and editor,” and wondering, “what happened?”

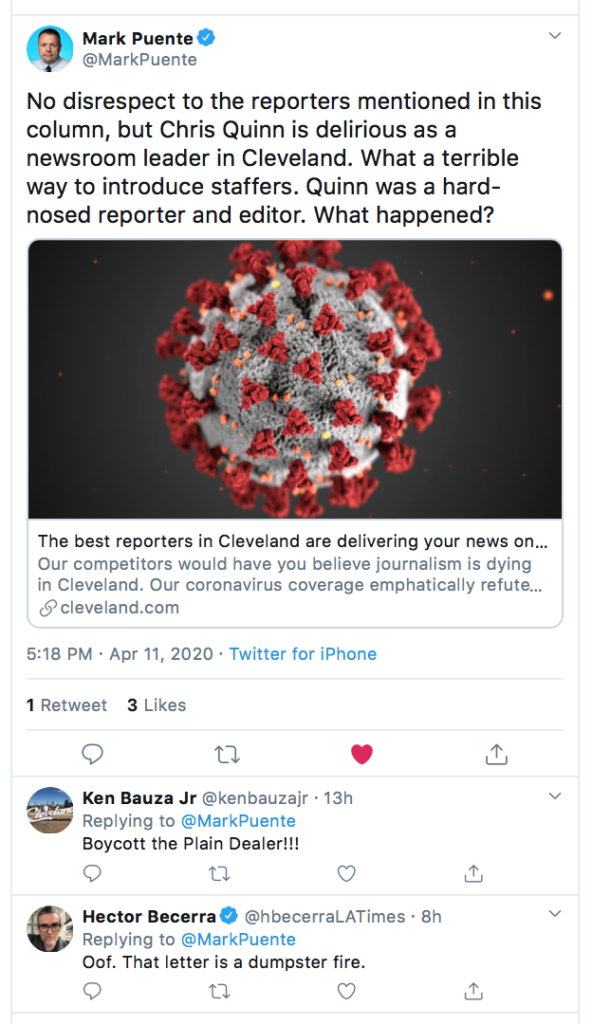

Others were less polite, like concerned citizen James Taylor, whose admittedly impolitic email prompted Quinn to fire off a few more paragraphs summarily maintaining his denialism regarding the PD layoffs while also bashing the City’s only other newspaper, the alt-weekly Scene, as being “of the lowest quality,” adhering to no journalistic standards, and consisting of “misinformed ranting based on almost no reporting and outrageously flawed conclusions.”

Of course, it’s all too easy for Quinn to punch down like this at Scene, which even in the best of times operates with a fraction of the resources that Cleveland.com has at its disposal in the worst. But it’s worth considering what it means that Quinn would so blithely ascribe “dubious motives” to anyone suggesting that it’s better for a City to have 350 reporters working for its only daily paper than only 63 of them.

In so casually dismissing the notion that a City with 80% fewer journalists is going to be 80% less informed, Quinn essentially admits to a view that there’s only so much the public needs to know. This is entirely consistent with a phenomenon long observed by America’s most incisive media critics, by which corporate media “artificially narrows the range of argument” on issues of public concern “long before you get to hear it.” As the basic thesis advanced by Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman in their seminal 1988 book, Manufacturing Consent, holds, “management of public opinion in capitalist democracies rarely takes the form of overt propaganda or censorship, but is instead achieved through vigorous policing of what constitutes acceptable opinion.”

It’s also telling that Quinn offers little more than a broad gesture at Cleveland.com’s prolific coronavirus coverage as evidence for his claim that journalism in Cleveland is in fact thriving. Of course, if it bleeds it leads, and nothing drives pageviews like anxiety over a deadly viral pandemic. Nevermind the difference between quantity and quality, and that Cleveland.com’s pages are largely silent as to the structural inequities causing socioeconomically disadvantaged populations to be disproportionately impacted by COVID-19.

It’s also telling that Quinn offers little more than a broad gesture at Cleveland.com’s prolific coronavirus coverage as evidence for his claim that journalism in Cleveland is in fact thriving. Of course, if it bleeds it leads, and nothing drives pageviews like anxiety over a deadly viral pandemic. Nevermind the difference between quantity and quality, and that Cleveland.com’s pages are largely silent as to the structural inequities causing socioeconomically disadvantaged populations to be disproportionately impacted by COVID-19.

Not to be too hard on Mr. Quinn, as he’s just one person who could only do so much under these circumstances even with the best of intentions. But the very least he could do is acknowledge that even if he somehow doesn’t believe in the necessity of adversarial journalism to a well-functioning democracy, many of his colleagues and fellow citizens still do; the recent developments at the PD serve to substantially amplify these concerns; and lashing out with insults in response to those who raise them is simply unacceptable from someone in his position. If journalism really isn’t going to be dead in Cleveland, it will need leaders who can manage at least this much.

I’ve reached out to Quinn for comment and will update this post re: his response. In the meantime, here are a couple of related pieces from Cleveland’s other paper:

Does Cleveland.com Editor Chris Quinn Hate Journalists as Much as it Sounds Like He Does?

Hope everyone’s week gets off to a good start and that Mr. Quinn, especially, has himself a better one.

—–

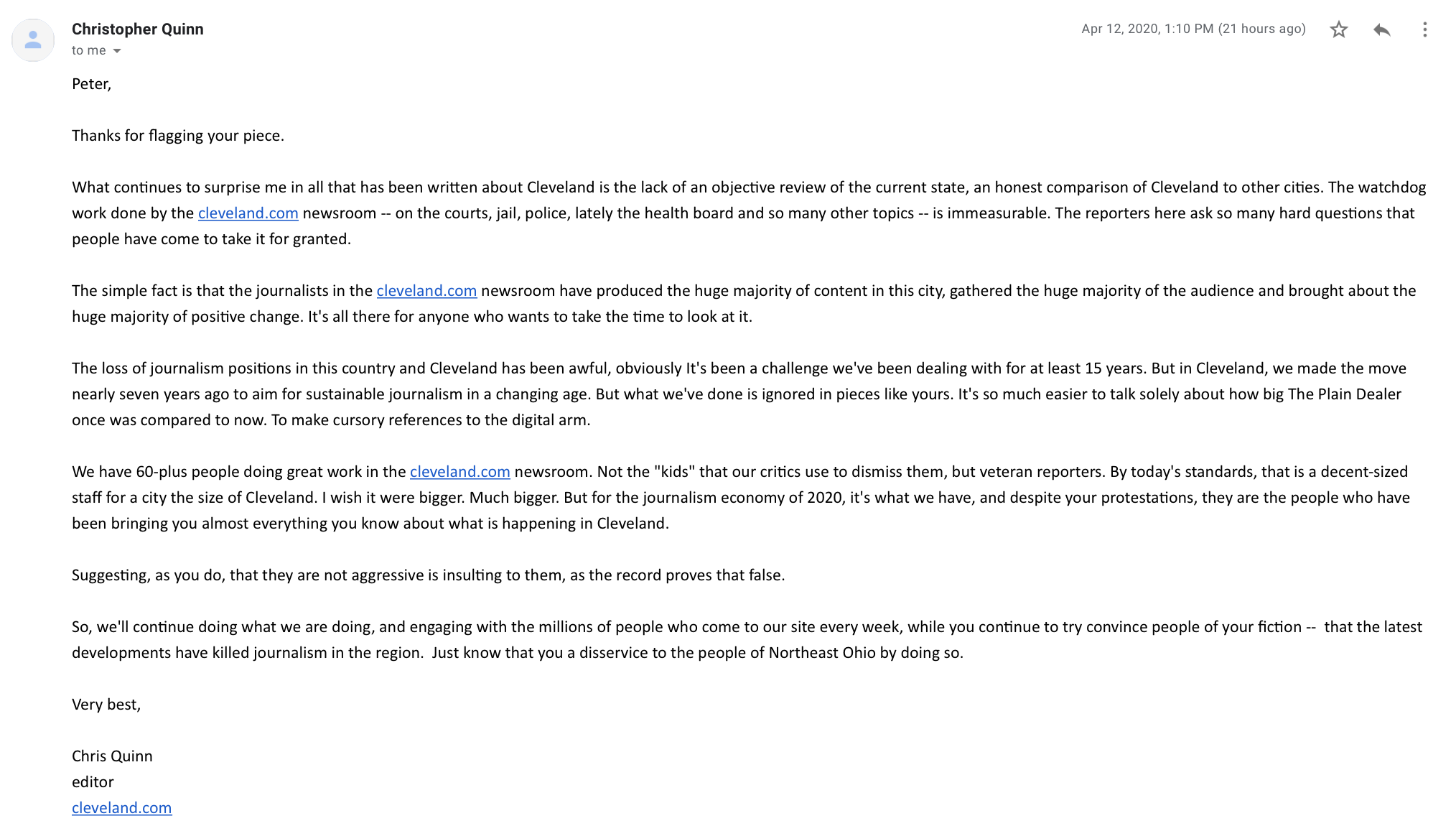

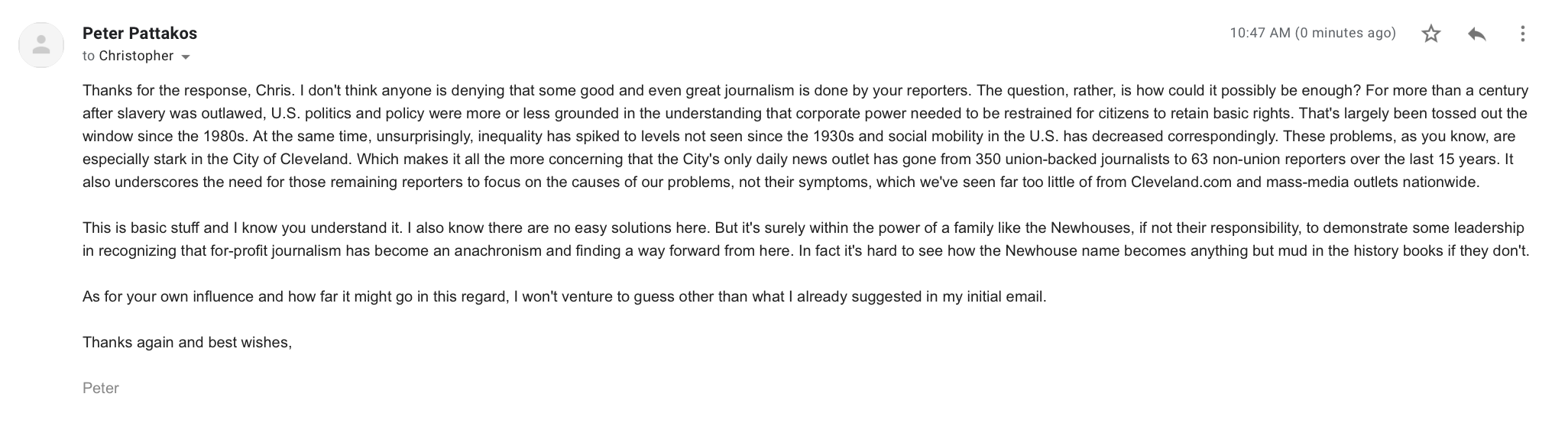

UPDATE: Mr. Quinn’s emailed in response to this post, which follows below, along with my reply (click twice to enlarge).